Exploring Seljuk Architecture in Konya: A Journey Through History

Let us envision the Seljuks as a movement; a massive surge of immense waterways rushing from the Far East, carrying cultural sediments from regions such as the Central Asian Steppes, Transoxiana, the Fertile Crescent, and Beth Nahrain, ultimately culminating as a fertile and diverse delta of cultures united in Anatolia.

During their gradual establishment in Asia Minor, the Seljuks developed a distinctive culture that engendered unique forms of expression, transcending the norms typically found in the expanse stretching from China to Anatolia.

In this blog, whenever we refer to a new architectural form or an artistic element they have contributed to the world's cultural heritage, we should keep this movement in mind to better understand the unique position they occupy in the realm of heritage and appreciate what the remnants of their era signify.

But who were they?

The Seljuks descended from the Oghuz Turkic people of Central Asia, who settled around the Aral Lake in the 10th century. By the 1070s, when they established their capital in Konya in Anatolia, they remained a semi-nomadic, semi-urban society. The nomadic Seljuks embodied the cosmos: they were untethered to any location, representing the boundless steppe they traversed, and with merely a temporary tent settlement, the vastness of the land served as their home. Between the earth and the skies, they were guided by countless spirits and omens. They acted as intermediaries, as shamans.

The settled Seljuks fostered Islamic scholarly learning through the madrasas they established.

They also initiated the creation of the State, as they were now anchored to the land, becoming stat-ic. Nonetheless, their beliefs were not strictly orthodox: with Sufi thinkers like Muhyiddin ibn al-Arabi, Mevlâna Celâladdin Rumi, Yunus Emre, and Haci Bektaş Veli, the world became a stage for “a thousand and one appearances,” all leading to “a multiplicity in the One.” This somewhat mirrored the nomadic worldview; one’s role in the cosmic order was one of harmony, which profoundly influenced Seljuk art, featuring geometric shapes of various symbols such as planetary systems, animal representations, and plant motifs carved into infinite patterns.

What were these patterns?

Examples such as a Qur’an stand, rahle, adorned with depictions of a double-headed eagle and lions, portal designs showcasing Asian zodiac animals in the intrados, and a portrayal of a bull and lion engaged in a fight (figuratively representing “night and day”, “the moon and the sun”, constellations of Taurus and Leo, contrasts of light and darkness, etc.) demonstrate how the Seljuks presented a genuine liberal synthesis for cultural unification to the world.

The Seljuks were like no others

The dual characteristics of the Seljuks gave them a unique trait that set them apart from others: they possessed a strong tolerance for urban societies, allowing them to effectively integrate key elements from these environments and ultimately forge their own identity.

The Seljuks left their permanent mark

In a relatively short period of about 250 years, amidst a landscape rife with intrigues and plots, and under the weight of external pressures and internal conflicts, the Seljuks embarked on an ambitious construction initiative – especially noteworthy given the era in which they lived. Records indicate that they adorned Anatolia with approximately 1,100 structures, comprising 115 mosques, 144 masjids, 64 dervish lodges, 145 tombs, 135 madrasas and medical institutions, 15 dârülkurrâs (classrooms), 179 caravanserais (khan/hans), 70 public baths, 49 bridges, 24 fountains, and 48 palatial residences. Over half (55%) of these structures remain, albeit some are in significant disrepair.

This impressive undertaking was supported by a total of 288 patrons, including both sultans and state officials, among whom there were also 34 women.

As for the architects, draftsmen, and other artists, out of the 60 names recorded, only 9 were based in Anatolia; the rest hailed from various backgrounds such as Armenians, Byzantines, Syrians, or Iranians. The inclusion of foreign artists and their cultural influences in Seljuk designs indicates that artists enjoyed a degree of creative freedom within Seljuk territories.

Konya marked the emergence of a capital city, and this article will transport you back to those days.

Here, you will embark on a journey through significant Seljuk architectural wonders like Alâeddin Mosque, Sâhib Ata Complex, Karatay Madrassa, İnce Minareli Madrasa, and Zazadin Caravanserai.

Alâeddin Mosque

Morning light streams through the arched windows of Alâeddin Mosque, casting a glow on dust particles that float above the 12th-century ebony minbar. This is not merely an artifact behind ropes - it is a living piece of history, its delicate carvings of vines and stars reflecting the Seljuk concept of cosmic harmony. The minbar carries the name of its maker, Mengi Berti of Ahlat, dated 1155, marking it as the earliest recorded masterpiece of Seljuk art in Anatolia.

The mosque complex conceals enigmas within its very stones.

On either side of the courtyard stand two mausoleums - one a vacant marble shell, halted mid-construction, the other a decagonal marvel adorned with greyish-blue tiles. The latter tomb contains the remains of almost all Seljuk sultans apart from İzzeddin, whose coffin was transported to Sivas, possibly due to his infamous rivalry with his brother Alâeddin. The unoccupied tomb poses a silent question about Seljuk history.

Sâhib-i Ata

In another part of the city, the Sâhib-i Ata Complex narrates another segment of the Seljuk tale. Constructed during the Mongol menace by Vizier Sâhib Ata, the complex harmonizes mosque, tomb, and dervish lodge into a cohesive stone symphony. The entrance itself mesmerizes with its muqarnas vaulting and calligraphic bands, while within, sunlight pours through intricately pierced domes, casting ever-changing geometric patterns on the floor. This was architecture as a form of spiritual practice - every arch and tile sharing Sufi secrets.

İnce Minareli Madrasa

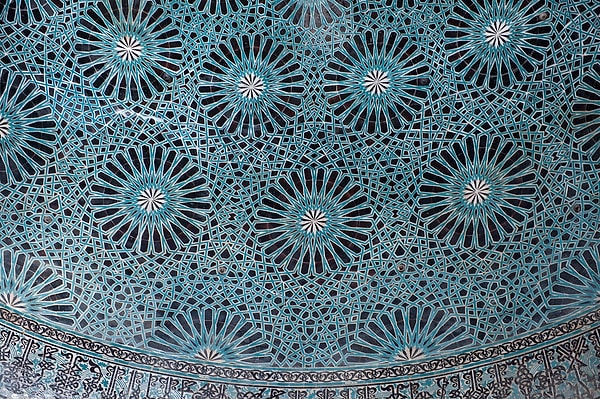

The İnce Minareli Madrasa nearby displays its history openly. The 'Slender Minaret' that lends its name to the structure stands alone since lightning struck down its companion in 1901. However, the real wonder is found in the portal’s stonework - Trees of Life combining with stylized eagle motifs, their designs foreshadowing European Baroque by centuries. Inside, the dome glimmers with turquoise bricks arranged in patterns identical to those still crafted into Konya’s carpets today.

Karatay Madrasa

Not all Seljuk benefactors aimed for recognition. At Karatay Madrasa, Vizier Celâleddin Karatay intentionally excluded his name from the building, leaving only discreet hints about its origin. The Syrian-inspired marble inlays and dome inscribed with the names of prophets indicate the craftsmanship of artisans from Damascus, perpetuating the Seljuk legacy of cultural amalgamation.

Zazadin Han

On the outskirts of Konya, Zazadin Han rises majestically from the plains. This caravanserai, constructed by the contentious vizier Sâdeddin Köpek, once provided merchants with complimentary lodging, medical assistance, and even shoe repairs. Now, standing in its vast courtyard, one can almost hear the sounds of camel bells and blacksmiths' hammers that once filled this space.

Source: Anadolu Ajans

What distinguishes these structures is not solely their age or beauty, but their ongoing functionality as lively spaces.

Students still engage in studies in madrasas, worshippers gather for prayer in mosques, and travelers find refuge in restored caravanserais. The Seljuks constructed not merely for posterity, but for eternity - and traversing through Konya today, it is evident they accomplished their goal.

Keşfet ile ziyaret ettiğin tüm kategorileri tek akışta gör!

Send Comment