6 Masterpieces Of Dali And Their Meanings

6 Masterpieces Of Dali And Their Meanings

You have probably encountered much strange news about the insane Dali. However, I have yet to come up with an analysis of what his works are telling us, and I have prepared a Onedio content that deals with this issue and which I think might be useful to people who are curious about it

When I know the find stories about works of art, I think that it's easier and more accurate to communicate with them.

Let's see what his works have been telling us all along.

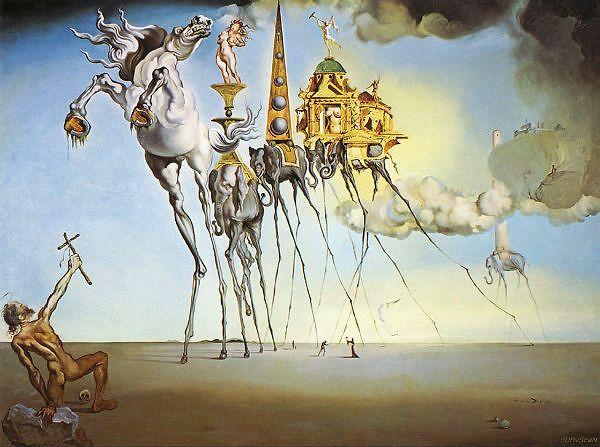

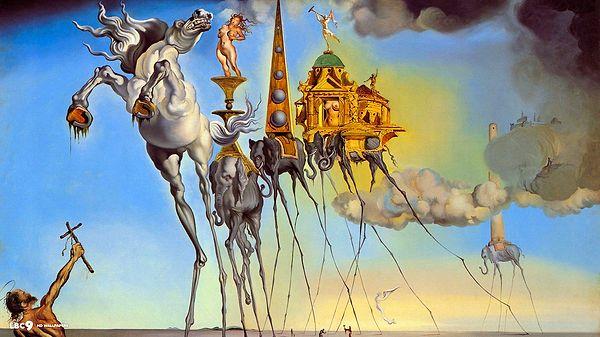

1. The Temptation of St. Anthony

All of the objects and figures in Dali's most famous paintings, Temptation of St. Anthony have meanings.

Dali often included symbolic meanings in his paintings. This work is typical of Dali examples.

In the researches I've done, I saw that St. Anthony is Padova Antonio. The reason for being a subject matter is that at the age of fifteen he encountered the devil and fired him from there by drawing a cross with his hand. At the same time, he was retreated many times in order to escape from all worldly desires, and also migrated to distant places. (I guess the readers who are Catholic will probably recognize him.)

In fact, this information brings out the main theme of the picture. It can only be Antonio who is lifting the cross ing the front. The skull standing right next to his right foot represents death. This is why he was protesting against worldly desires.

Religion, criticism, and desire object

If there is a horse in art history that's rampant, you know that there is power, mightiness, and courage. The most commonly used method in art language is a lion or a rampant horse. The master painter, aware of this, took the situation a step further and included the senses of lust into his work of seduction. Here the horse is the predator of sexual impulses.

The elephant right behind is carrying a golden pedestal on its back and a woman who's calling for sexual desires. This is also the object of desire. It is no coincidence that most of the today's advertisements for males are played by women. An object of desire appealing to man's direct impulses awaits Antony with all her charm.

The elephants that follow are like a temple. He's probably criticizing religion here. The naked bodies in religious structures are a criticism against corruption. Here, religions' desperation might be expressed against impulses. Because they are carried by pretty fragile legs.

2. The Persistence of Memory

The meaning behind Surrealist Salvador Dali's artistic masterpiece The Persistence of Memory (1931) is not easy to grasp. In the painting, four clocks are prominently on display in an otherwise empty desert scene. While this might seem uncanny enough, the clocks are not flat as you might expect them to be, but are bent out of shape, appearing to be in the act of melting away. In classic surrealist manner, this weird and unexpected juxtaposition poses a lot of questions right up front. First off, why are these clocks melting? Why are the clocks out in the desert? Where are all the people?

Since the subject matter and content of the Salvador Dali's clocks painting seems illogical or irrational, one might be surprised by the very representational and nearly photographic quality of the painting, fitting well with Dali's own description of his art as being 'hand-painted dream photographs.' The concept of the 'dream' is integral in understanding Surrealism and plays a key role in the meaning of The Persistence of Memory, as well.

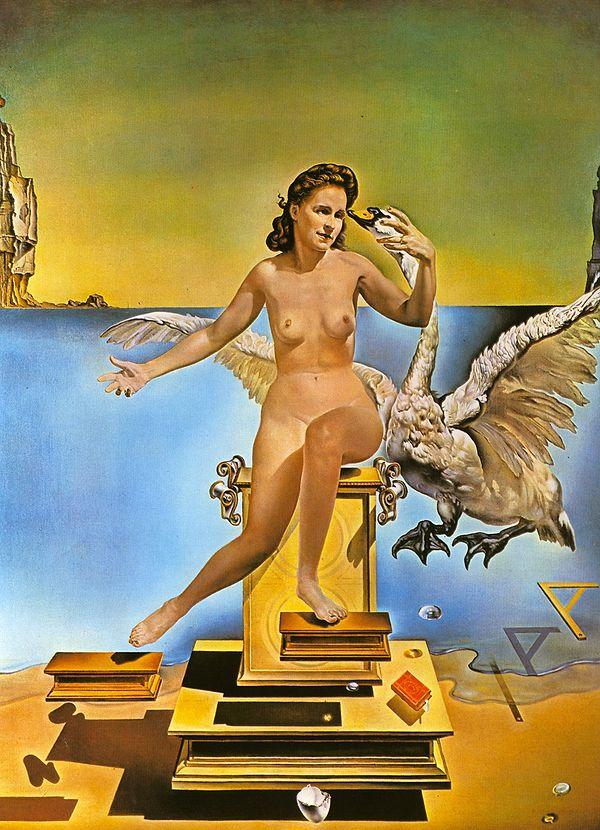

3. Leda Atomica

According to classical mythology, Leda was seduced by Zeus in the form of a swan, and, on the same night, made love to her husband, Tyndareus. Leda consequently bore two sets of twins: Helen (to become Helen of Troy) and Clytemnestra, and the Dioscuri-Castor and Pollux. Helen and Pollux - being the children of Zeus - were immortal, while the children of Tyndareus - Castor and Clytemnestra - were mortal. Dali identified with Leda's offspring, suggesting that he and Gala were twin souls - an especially appropriate analogy given Gala's Christian name, Helena Dimitrievna Diakonova. It is not as Helen, however, but as Leda herself that Gala appears in Leda Atomica - perhaps suggesting her role as a substitute for the artist's dead mother. Her left-hand with conspicuous wedding band sweetly caresses the head of the Zeus-swan - the lone element in the painting that fails to cast a shadow, thereby indicating its ethereality.

While Dali's 1961 Leda and the Swan, described by the artist as 'spermatic,' exaggerates the Leda myth's carnality, as captured by such artists as Michelangelo, and Peter Paul Rubens, Leda Atomica eschews concupiscence in favor of a more Apollonian subject, akin to 1508 painting, Leda and the Swanby Leonardo da Vinci.

After the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Dali took his work in a new direction based on the principle that the modern age had to be assimilated into art if art was to be truly contemporary. Dali acknowledged the discontinuity of matter, incorporating a mysterious sense of levitation into his Leda Atomica. Just as one finds that at the atomic level particles do not physically touch, so here Dali suspends even the water above the shore - an element that would figure into many other later works. Every object in the painting is carefully painted to be motionless in space, even though nothing in the painting is connected. Leda looks as if she is trying to touch the back of the swan's head, but doesn't do it.

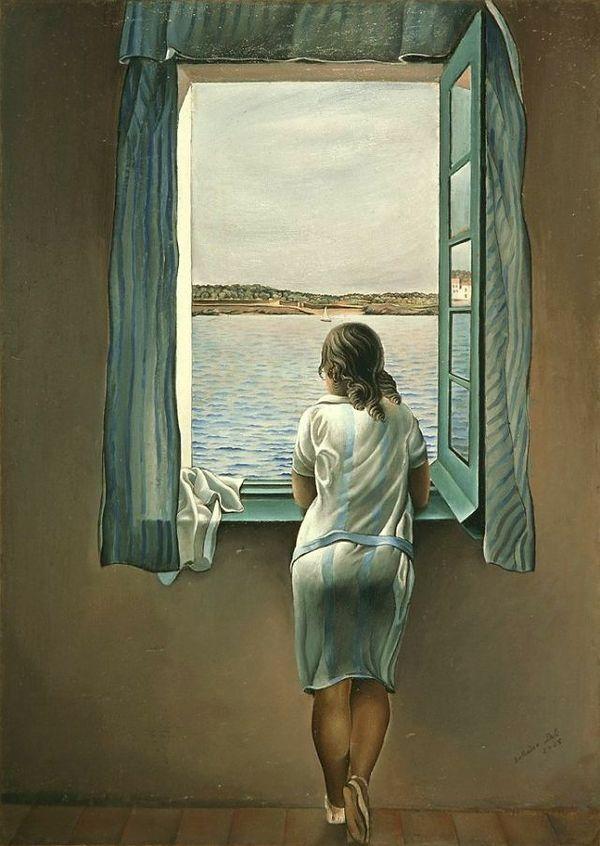

4. Figure at a Window

Dali's younger sister Ana Maria was a willing and favorite sitter in the 1920s, especially in the months leading up to his first solo exhibition, at the Galeries Dalmau in Barcelona. It is thus not surprising that his paintings of her reflect his experiments with various figurative styles. Dali paid special homage to Ingres in the catalog for the exhibition and the drawing of his father and sister is a superb essay in academic draftsmanship. At the same time, in the contrast between the delicately modeled faces and the simple linearity of the bodies he is looking towards Picasso's post-cubist return to the figure.

In several of his paintings, he explores a simplified representational technique, with smooth slightly geometrical rounded forms and flattened planes, as in Girl resting on her elbow - Ana Maria Dali, the artist's sister (Thought). Indeed in most of his figure paintings at this time, despite the obvious contrast with the Cubist and Purist works, there is an interest in surface pattern and abstract rhythm which derives from his avant-garde experiments. He is also exploring a wide range of earlier and contemporary figurative painting, including the Italian Novecento artists.

5. Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized By Her Own Chastity

The history of Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by Her Own Chastity, 1954, is closely connected to Dali's sister. In his scatological period - which to Dali's delight scandalized the surrealists - he had painted a picture of his sister, a rear view which emphasized the girl's behind.

The painting documents Dali's interest in exaggerating the representation of the female form and the possibilities of an abstracted background. The main force within the painting is clearly its sexual allusion: the horned shapes hovering around the woman are overtly phallic, and the painting's title offers a direct clue about the aggressively sexual tone of the work. Dali's preoccupation with the phallus was a central theme throughout his career, though the degrees to which his works were representational or abstract differed period to period.

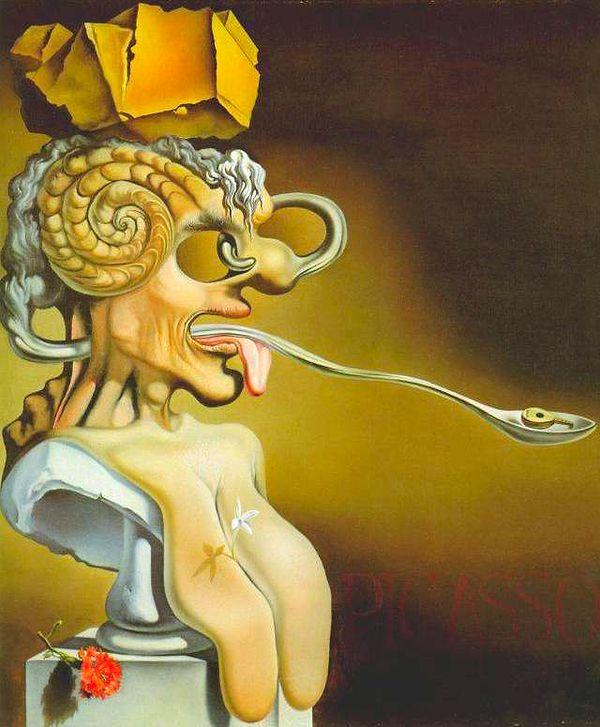

6. Portrait of Picasso

The surrealist portrait painting of Pablo Picasso by Salvador Dali is infused with symbolic messages and meanings as Dali’s most famous works are.

Basically, instead of a direct face, it is a portrait of Picasso’s bust sculpture. The base of the bust is made out of the regular white stone out of which most bust-sculptures are made of. But, the upper part is covered with skin. There is a white flower in the distorted chest of the bust, while a red one, is laying at the feet of the bust.

The head is much more distorted than the chest with empty eye sockets, horned nose, open mouth with drooling tongue. The depicted brain resembles a goat’s round horns. It is covered from top to back of the head with unnaturally thick white hair which seems to be made out of the same material as the white base of the bust. A thick thread of hair is prolonged from the back end of the hairs which comes out through the mouth and turns into a prolonged spoon in front of the distorted face. The spoon holds a little Lute at the end. Lutes are the symbol of love or sexual motifs. That symbolism is backboned with the drooling tongue. Over the head lingers a yellow rock.

The background is made out of two shades of brown with dark brown at the corners while the brown with yellowish tint covers the bust itself.

Keşfet ile ziyaret ettiğin tüm kategorileri tek akışta gör!

Send Comment